The Woman in White, l’espace blanc

et la technologie d’impression

au milieu de l’ère victorienne

- Mary E. Leighton - Lisa Surridge

_______________________________

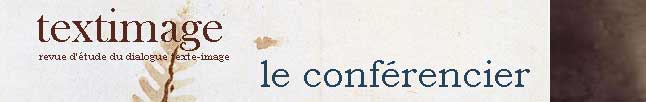

Fig. 10. J. McLenan, The Woman

in White, 1860

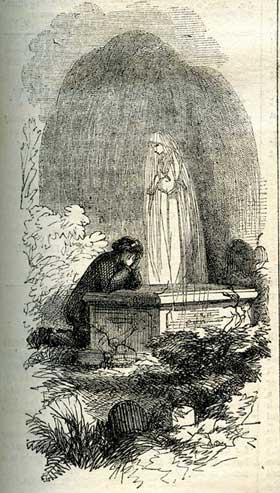

Fig. 11. J. McLenan, The Woman

in White, 1860

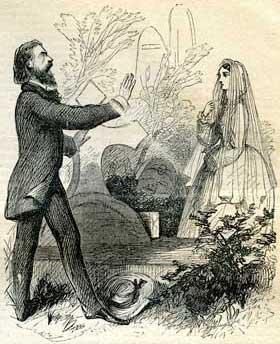

Fig. 12. J. McLenan, « The nurse came quickly

around the corner of the wall... », 1860

La scène la plus saisissante du romana lieu lorsque Hartright, en deuil, se rend sur la tombe de Laura (qui s’avèrera être en définitive la tombe d’Anne). Alors qu’il arrive, il voit deux femmes voilées approcher : Marian et Laura. Cependant, Hartright ne reconnaît pas cette dernière jusqu’à ce qu’elle lève son voile au moment où elle se tient juste au-dessus de la pierre tombale sur laquelle la date de sa mort est inscrite. Dans cette scène-pivot du roman, le trope verbal de répétition atteint son paroxysme. Hartright prend alors le style auparavant associé à Anne Catherick :

Above it, there were lines on the marble, there was a name among them which disturbed my thoughts of her. I went round to the other side of the grave, where there was nothing to read – nothing of earthly vileness to force its way between her spirit and mine.

I knelt down by the tomb. I laid my hands, I laid my head on the broad white stone, and closed my weary eyes on the earth around, on the light above. I let her come back to me. Oh, my love ! my love ! my heart may speak to you now ! It is yesterday again since we parted—yesterday, since your dear hand lay in mine – yesterday, since my eyes looked their last on you. My love ! my love ! (…)

Beyond me, in the burial-ground, standing together in the cold clearness of the lower light, I saw two women. They were looking toward the tomb ; looking towards me.

Two.

They came a little on ; and stopped again. Their vails [sic] were down, and hid their faces from me. When they stopped, one of them raised her vail. In the still evening light I saw the face of Marian Halcombe.

Changed, changed as if years had passed over it ! The eyes large and wild, and looking at me with a strange terror in them. The face worn and wasted piteously. Pain and fear and grief written on her as with a brand.

I took one step towards her from the grave. She never moved – she never spoke. (…)

The woman with the vailed face moved away from her companion and came toward me slowly. Left by herself, standing by herself, Marian Halcombe spoke. It was the voice that I remembered – the voice not changed, like the frightened eyes and the wasted face.

"My dream ! my dream !" I heard her say those words softly in the awful silence. She sank on her knees, and raised her clasped hands to the heaven. "Father ! strengthen him. Father ! help him, in his hour of need".

The woman came on – slowly and silently came on. I looked at her – at her, and at none other, from that moment (…)

The woman lifted her vail.

Sacred

TO THE MEMORY OF

LAURA,

LADY GLYDE –

Ce passage est saturé par les figures de la répétition : 1) l’anaphore, où les mots se répètent au début de phrases ; 2) l’épistrophe, où les mots se répètent à la fin de phrases ; 3) l’anadiplose, où le premier mot de la phrase répète le dernier mot de la phrase précédente ; 4) l’épanalepse, où un terme ou un segment de phrase sont répétés. L’effet est similaire à l’homiologie parce qu’après une certaine saturation, le sens est évacué au lieu d’être renforcé. Le passage crée donc son effet sensationnel en évoquant le tic verbal de répétition d’Anne sur la tombe de Laura (qui est en réalité la tombe d’Anne) alors que Hartright voit Laura (sans la reconnaître).

Au même moment, le récit illustré du Harper’s supprime toute perspective pour la figure de Laura (figs. 10 et 11) : elle n’est plus en trois dimensions mais plate, représentée par un espace blanc avec seulement un contour. Paradoxalement, cette représentation visuelle associe la jeune femme à un fantôme ou à un revenant au moment exact où elle apparaît pourtant en chair et en os. De plus, le récit annule le sens de l’inscription sur la pierre tombale : si Laura est vivante, alors les lettres noires gravées sont littéralement et métaphoriquement creuses.

A partir de ce moment, le roman devient une investigation de ces contradictions pour mettre fin à leurs effets sensationnels. Décédée, Anne disparaît du présent temporel de l’histoire ; elle n’apparaît plus que dans des analepses. Dans les illustrations, l’amalgame troublant de sa représentation visuelle avec celle de Laura disparaît : son image gagne progressivement en épaisseur et en profondeur : Laura gagne peu à peu en consistance physique.et les illustrations montrent de plus en plus de traits noirs (fig. 12). D’une manière remarquable, Hartright n’emploie jamais un procédé juridique pour démontrer que Laura n'est pas morte. Marian et lui ont recours à la narration : ils racontent l’histoire de la conspiration, et fournissent des preuves visuelles : ils montrent Laura aux locataires de la propriété pour prouver son identité. Ils ne produisent donc pas des preuves légales mais une multiplicité d’histoires, qui se substituent l’une à l’autre. C’est seulement après avoir offert ces preuves narratives qu’ils peuvent légitimement effacer au ciseau le nom de Laura sur la pierrre tombale, laissant un espace vide qui portera plus tard celui d’Anne.

[20] Ibid., 19 mai 1860, p. 311.