Representing Evolution: A Case Study

in Visual Narrative

- Richard Somerset

_______________________________

Fig. 10. Th. Carreras, “The Ancient

Fish & their Huge Rival”, Winners in

Life’s Race, 1882

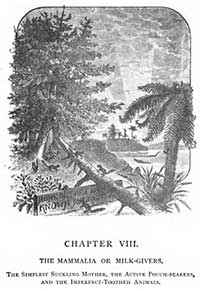

Fig. 11. Th. Carreras, “Home of the

Far Known Milk Givers”, Winners in

Life’s Race, 1882

Some apparently sober and understated picture headings reveal themselves to contain hidden narratives of frontier-crossing when read in parallel with the text of the associated chapter. This is the case of the scene heading chapter 2, which introduces the first main vertebrate type, the fish (fig. 10). At first the illustration seems banal enough, a straightforward depiction of a scene in an ancient sea without any flamboyant breaking of conventional frames going on. Even the title element seems more clearly demarcated as conventional and external to the scene, at least in comparison to our earlier examples. After reading the chapter, however, the significance of the two tiny crustacea appearing just below the title element becomes evident. Here are some excerpts of Buckley’s comments on the species depicted in the picture heading, the crustacean Pterygotus and an early “enamel-shielded” form of fish:

[This was] a time when the crustaceans were the most powerful animals in the world, and the huge lobster-like Pterygotus was the monarch of the seas. It was in the midst of a scene such as this that we first find the feeble ancestors of the Sturgeon and the Shark beginning to make their way in the world. ... These fish would keep out of the way of the Pterygotus because they were small and weak and he was large and strong. ... Yet they were the beginning of a powerful race of creatures, for they had the great advantage of a growing inside skeleton, which could vary and strengthen with their bodies from generation to generation, while their rivals, the Pterygotus and his companions, had only their heavy cumbrous armour with a mass of soft flesh inside, and were but lumbering creatures at best.

And so we find that as thousands and thousands of years rolled by, the descendants of the enamel-shielded fishes began to improve, and grew larger and more powerful as the generations passed on, till they became master of the shallow seas, and after awhile of the rivers and lakes. ... For this was the Golden Age of fishes, just before the time when the coal-forests grew; and the clumsy crab-like animals, and the trilobites, which had had their innings when the fish were small, now began gradually to be exterminated by their powerful enemies. Little by little they gave up the battle of life, and the larger ones died out altogether, leaving only those smaller crustaceans which did not clash with the fish (WLR, 37-40).

This is a good example of Buckley’s basic plot dynamic. Each one of “life’s children” has a turn to carry the torch, until eventually a higher form emerges, not necessarily bigger or stronger, but somehow better nevertheless; at this point the torch must be passed on to the next type and the former monarch retire to a new position somewhere near the bottom of the emerging hierarchy. Only if they accept marginality will their continued existence be possible. Returning now to the picture heading, it is easy to see how its construction is intended to materialise Buckley’s dynamic of change. The giant Pterygotus seems to dominate this world, and the small fishes in the background constitute no imaginable threat to his authority; but in fact the fish are destined to take over from the crustacean, and the giant of the centre will dwindle until it resembles the marginalised creatures at the bottom of the picture. Occupying a separate space marked off by the title-ribbon, these diminutive creatures do not participate in the principle scene; instead they constitute a sort of glimpse ahead to the future life of the Crustaceans after they have handed over power to the fish. So this apparently most naturalistic amongst Buckley’s scenes is really intended as the representation of an abstract dynamic of change.

Perhaps the most elaborately constructed picture-heading is that which marks the arrival of the mammals and which figures at the head of chapter eight (fig. 11). As in the other mammal scene already mentioned (fig. 9  ), this picture heading makes prominent use of a naturalised title element, a sort of carved plank which has somehow become ensconced in the scene. The element’s involvement is particularly strongly marked since its presence is required to sustain a fallen trunk which runs from the bottom right-hand corner of the image across the supporting title-element and on towards the centre of the composition. Around this trunk, and running along the top of it, are samples of the main animal type featured in this composition, the primitive marsupial, Microlestes [8]. Close to the base of the fallen trunk grows a single tree fern, while in the larger more central space towards which the other end of the trunk seems to point is a group of deciduous trees. In the background a group of “large swimming reptiles” (WLR, x) appear in the distance in front of a setting (or perhaps a rising?) sun. The frame is not as flamboyantly traversed in this image as it is in some, but it is far more marked on the right-hand side and top than it is on the left and bottom, where it tends to disappear behind the deciduous trees and the ground upon which the marsupials play. Having already established Buckley’s visual lexicon, the image is not difficult to read. The most significant ‘internal framing device' is the naturalised title element, and the fallen trunk traversing it translates the idea of the limit crossed; in this case we even have some creatures obligingly doing the crossing! The space is separated into three main zones: the seascape in the background, associated here with the once-dominant reptiles, now doomed to marginality as indicated by their tiny size; and the two spaces on either side of the internal framing device, associated with the older tree fern type of vegetation in the one case, and with the more ‘modern' deciduous trees in the other. In addition to the very clearly materialised frontier-crossing that dominates the action in the centre of the scene, the sunset/sunrise backdrop further accentuates the theme of fundamental change.

), this picture heading makes prominent use of a naturalised title element, a sort of carved plank which has somehow become ensconced in the scene. The element’s involvement is particularly strongly marked since its presence is required to sustain a fallen trunk which runs from the bottom right-hand corner of the image across the supporting title-element and on towards the centre of the composition. Around this trunk, and running along the top of it, are samples of the main animal type featured in this composition, the primitive marsupial, Microlestes [8]. Close to the base of the fallen trunk grows a single tree fern, while in the larger more central space towards which the other end of the trunk seems to point is a group of deciduous trees. In the background a group of “large swimming reptiles” (WLR, x) appear in the distance in front of a setting (or perhaps a rising?) sun. The frame is not as flamboyantly traversed in this image as it is in some, but it is far more marked on the right-hand side and top than it is on the left and bottom, where it tends to disappear behind the deciduous trees and the ground upon which the marsupials play. Having already established Buckley’s visual lexicon, the image is not difficult to read. The most significant ‘internal framing device' is the naturalised title element, and the fallen trunk traversing it translates the idea of the limit crossed; in this case we even have some creatures obligingly doing the crossing! The space is separated into three main zones: the seascape in the background, associated here with the once-dominant reptiles, now doomed to marginality as indicated by their tiny size; and the two spaces on either side of the internal framing device, associated with the older tree fern type of vegetation in the one case, and with the more ‘modern' deciduous trees in the other. In addition to the very clearly materialised frontier-crossing that dominates the action in the centre of the scene, the sunset/sunrise backdrop further accentuates the theme of fundamental change.

Pictorial sources and contrasts

This series of examples has served to illustrate how Buckley developed a visual language whose task it was to reinforce and to complete the challenging core concept she wished to communicate to her young readers, the concept of categorial change in nature. We have also remarked on the author's tendency to avoid frontal engagement with this issue in her text, preferring to deal with change allusively in the relatively safe meta-textual space offered by the sequence of ‘picture-headings'.

We have also seen that something similar can be said for other authors working in the ‘History of Life' genre, even though their illustrations were designed to suit the particular ideology the author sought to promote. However, it is important to realise that visual models for illustrators to work with were relatively scarce, the speculative reconstruction of prehistoric beasts being an art that was still in its infancy. It is therefore not surprising that representations considered successful tended to be recycled by other authors – even when they were backing a rival outlook. Buckley was no exception in this respect, and she borrowed freely from Figuier’s illustrations as well as those of other fixist authors. However, any such borrowings were always transformed, if only lightly, in order to produce a result that echoed the author’s preferred visual codes and conceptual orientations. Such manipulation of borrowed material is of course interesting for what it suggests about the particularity of our author’s visual and narrative strategies.

[8] Identified in the table-of-contents description of the scene.