Representing Evolution: A Case Study

in Visual Narrative

- Richard Somerset

_______________________________

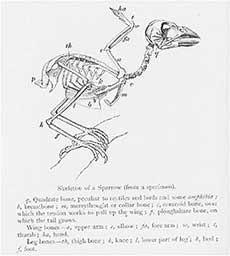

Fig. 3. Th. Carreras, “Sparrow”, Winners in

Life’s Race, 1882

Fig. 4. Th. Carreras, “Skeleton of a Sparrow”,

Winners in Life’s Race, 1882

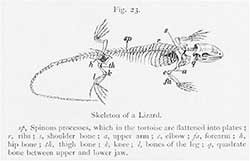

Fig. 5. Th. Carreras, “Skeleton of a Lizard”,

Winners in Life’s Race, 1882

Of course the story of Life could also be told in other ways, in order to suggest different dynamics. But quite significant variation could also be operated within the model conceived by Figuier; and in fact, his text was subjected to a form of manipulation by translators. Thus the English versions of La Terre avant le déluge, for example, were subtly realigned to suit the text to the Anglo-American ideological context: where the original French text was resolutely empirical and aggressively anti-development, the English versions soft-pedalled the empiricism to allow a greater space for providential design, and by the same token, for a dynamic of progressive change [4]. So, given the popularity and the relative adaptability of the Figuier model, there was initially no very strong impulse towards the formulation of alternative modes. It was not until the 1880s that the need to defend a form of developmentalism influenced by Darwinian evolution prompted some popularisers to attempt a novel approach to the ‘history of Life' genre. An interesting example can be found in the work of the important science writer and educator, Arabella Buckley; and it is to her most significant work in this domain, Winners in Life’s Race, that we accordingly now turn.

Buckley’s narrative: a typological framework

One of the most successful producers of science for children in the late nineteenth century, Buckley came to writing relatively late in her career, after eleven years’ work as Charles Lyell’s personal assistant – a position she lost only after the geologist’s death in 1875. Unmarried until 1884 at 44 years of age, she probably turned to writing out of economic necessity. Her first efforts were in the history of the natural sciences and – later on – in English history, but it was in the repackaging of science for children that she excelled. Perhaps her most successful title was the first, The Fairyland of Science (1879), a series of ‘talks' in which aspects of the natural world as perceived by the scientist are presented in the magical terms usually associated with fantasy stories. Almost equally successful were the next two titles, Life and her Children (1880) and Winners in Life’s Race (1882), respectively presentations of the invertebrate and the vertebrate classes of animals, and thus together forming a complete survey of nature and its workings. Although Darwin was barely mentioned in either text, it is clear that one of Buckley’s unstated missions was to introduce her young readership to a world-view influenced by Darwinian thought; a delicate subject to bring before children so soon after the ‘Monkey debate' of the 1870s! Clearly, Buckley had to be very careful about the form of Darwinism she presented, and most of all, how she presented it. It was perhaps in response to such pragmatic considerations, then, that she chose to focus on the immediate task of importing changefulness into the realm of nature, and on giving that changefulness the only form – moral and progressive – that would be acceptable to her middle-class readership. In promoting this vision, Buckley based her narrative on hierarchies of typology rather than on the chronology of descent, and then relied largely on suggestive illustrations to establish the required link between the two. Unlike Figuier’s naturalistic representations, Buckley’s scenes served not as ‘witnesses' of the successive stages of the past world, but as abstract representations of the idea of the limits of classes of being, and especially, the meeting points between them. The key concepts in these illustrations, I would suggest, are frames and limits, thresholds and points of passage.

The best way to get a feeling for Buckley’s ‘typological' approach to the telling of the story of Life will be to start with the specimen diagrams which form an integral part of the text itself. These also featured heavily in Figuier’s narrative, but naturally enough for him they mostly depicted either fossil remains or the reconstruction of the extinct life-forms they represented. In Buckley’s work, on the other hand, only one specimen diagram depicts the remains of an extinct species; all the others represent the familiar beasts of the modern world. How can this approach be made to work towards Buckley’s goal of defending a developmental understanding of the story of Life? The strategy can be summed up as one that based its empirical credentials upon the participatory observation of modern nature, and then applied these findings to the past history of Life by a process of analogy. A few examples will illustrate the technique.

In presenting these specimens Buckley often inserted two illustrations, as can be seen in figures 3 and 4: the first depicted the animal as normally seen; and the second presented the same animal in the same posture but with the soft tissue removed to reveal the skeleton beneath. In addition, each of the skeleton illustrations featured a common pattern of labelling (compare figs 4 and 5) – a scheme which allowed Buckley to draw the reader’s attention to the unexpected similarity of anatomical construction in these apparently very different sorts of animals. The educated gaze, she thus suggested, is able to see beyond the apparently radical differences between these classes of animals and to discern elements of structural convergence. This underlying similarity can act as the basis of an implied narrative of common descent. In the text, Buckley worked up this sense of connection by the extensive use of two related metaphors, the first centred on the notion of the family and family relations, and the other on the notion of the competitive race. These are already visible in Buckley’s titles, Life and her Children, and Winners in Life’s Race. Briefly, the first metaphor works to join different animal-types together under the auspices of a shared genealogy as the ‘children' of a loving mother (Nature); while the second serves to introduce the notion of dynamic hierarchy or progress, with some ‘children' becoming progressively more advanced, physically or morally, than others [5].

Buckley’s implied narrative: a story of limits and thresholds

We have already stated that Buckley’s text focuses on the familiar animals of the modern world, while the extinct species of former times are typically mentioned only in passing. Indeed, such passages as relate directly to the geological past seem to be little more than embellishments in a text whose core structure, and overwhelming bulk, is devoted to a typological survey of modern forms. For example in the chapters on fish where the most significant foray into the past occurs, this digression occupies a mere seven pages out of a total of fifty (WLR, 35-42). The rest is almost exclusively occupied with a survey of modern fish types, designed to give body to the idea that amongst these species, there exist more or less ‘modern' or ‘ancient' types. The shark and the sturgeon, for example are described as “old-fashioned”, while the apparently modest minnow is an exemplar of the modern bony fish, characterised by remarkable agility and a sort of incipient moral sense discernible in the care that some species devote to their young.

[4] Figuier’s work was translated as The World Before the Deluge: six different editions were produced between 1865 And 1891. For a detailed discussion, see Richard Somerset, ‘Textual evolution: the translation of Louis Figuier’s La Terre avant le déluge’, The Translator, Volume 17, Number 2, 2011, pp. 255-74.

[5] For a fuller discussion of Buckley’s narrative strategies see Richard Somerset, ‘Arabella Buckley and the Feminisation of Evolution as a Communication Strategy’ in Nineteenth-Century Gender Studies, Special issue: “Women Write the Natural World”, summer 2011.