Teaching Christian Eyes

- Lee Palmer Wandel

_______________________________

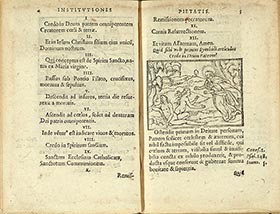

Fig. 10. P. Canisius, Institutiones Christianae

Pietatis, 1575

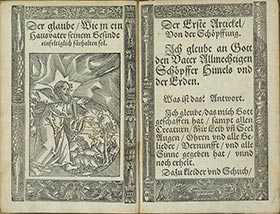

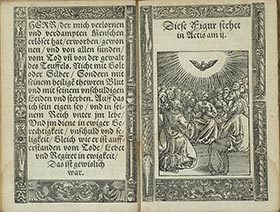

Fig. 11. M. Luther, Enchirion, 1531

Fig. 12. M. Luther, Enchirion, 1531

Catechesis then moves to the Apostles’ Creed (fig. 10), which Canisius teaches in the traditional division of twelve articles [9]. The prompt for the first article, “I believe in God the Father,” precedes the woodcut, which is then followed by the catechumen’s answer. The prompt does not name, “Creator”, but the image renders a single moment in the Genesis narrative, the creation of Eve. The woodcut is not, however, literal. Genesis 2 : 21-23 reads :

And the Lord God cast a deep slumber on the human and he slept, and He took one of his ribs and closed over the flesh where it had been, and the Lord God built the rib He had taken from the human into a woman and He brought her to the human. And the human said:

“This one at last, bone of my bones

and flesh of my flesh,

This one shall be called Woman,

for from man was this one taken” [10].

This image, which in the codex precedes the page with the woodcut of the single figure of Charitas, shares with Charitas its emphasis on the affective connection between God, here the Father, and humankind. Here, God’s arms and hands are extended and his person is represented as though in movement towards Eve, who rises towards God from the sleeping Adam. God radiates here, the sign of that radiance surrounding his head. While the catechumen learns from the text beneath the woodcut of the creation of heaven and earth, the image presents God as Creator of humankind – a more intimate relationship.

There is no human in the image of creation that prefaces the Creed in the Enchiridion (fig. 11). In its placement of God outside Creation and in its rendering of Creation as a circle, this woodcut is evocative of Cranach’s Genesis from the Luther Bible. In the Cranach rendering of Creation, God is outside of, above on the plane of the image, and looking at “Creation”, which is rendered as a series of concentric circles, each one of which marks an act of creation, from the void through the sun and moon, through the separation of the waters and land, to the plants and the creatures that fly and walk, at the center of which stand Adam and Eve. In the woodcut in the Enchiridion, God stands to the side, his hands and moving legs far more reminiscent of Christ as rabbi. Creation here is also radically simplified: not the making of Eve, but the creation of goats and bucks and trees.

The relationship of catechesis and image, moreover, is once again different. While the image invokes—but does not render either in its temporal sequence or in the fullness of all that is created—the Genesis narrative, while looking at that image, the catechumen explains the meaning of the words, as the facing page specifies :

The First Article, Concerning Creation

I believe in God the Father Almighty Creator of Heaven and the Earth

What is that? Answer.

I believe that God has created me, along with all creatures, has given me body and soul, eyes, ears and all limbs, reason, and senses, and still preserves them.

Creation, as Luther’s catechisms specify, primarily concerns God’s care of humankind – clothes and shoes as well as senses and limbs. The image, then, acquires another reading: the creatures who figure in the woodcut, a goat and a buck, provide food.

Luther divided the Apostles’ Creed into three articles, Creation, Redemption, and Holiness:

Thus the first article concerning God the Father, explains creation; the second, concerning the Son, redemption; the third, concerning the Holy Spirit, being made holy. Hence the Creed could be briefly condensed to these few words: “I believe in God the Father, who created me; I believe in God the Son, who has redeemed me; I believe in the Holy Spirit, who makes me holy.” One God and one faith, but three persons, and therefore also three articles or confessions [11].

In the 1547 Enchiridion, the catechism’s teaching of the Creed is accompanied by three images. The number reinforces Luther’s distinctive division of the Creed into three articles. Each woodcut visualizes how that part is to be understood. The first woodcut, as we have seen, visualizes Creation, invoking the opening image of Genesis even as it renders a creation that feeds humankind.

The woodcut for the second person renders the Crucifixion (fig. 12). The Crucifixion was perhaps the single most familiar image of late medieval Christianity, its central figure invoked so many affiliations – of sacrifice and redemption, but also suffering, the cross, the Passion, there in the lance that would pierce Christ’s side. Following the teaching of the catechism, this woodcut visualizes redemption, a major theme of Luther’s catechisms. Here, as in the predella in Wittenberg, the crucified Christ is spatially at center, the cross just below the frame of the image, dividing the image by its presence. Here, as with the Ten Commandments, scriptural references precede the woodcut, providing a Scriptural anchor for the image. Here, even more than with the Ten Commandments, the biblical narrative founds the image, which points towards more than one moment in the narrative, by the simultaneous presence of Mary and John on the left, who so often figure in Andachtsbilder, and behind them and to the right, soldiers, who are dressed not as Roman centurions, but as sixteenth-century Jünker.

The second woodcut (fig. 12) faces the page on which is printed the rest of the catechesis of the first part, God as Father and Creator. Word and image thus link two of the persons of the one God Luther’s catechisms taught. In like manner, the third image (fig. 13) faces the catechesis of the second person of the Trinity, once again, word and image binding, this time, the second and third persons of the Trinity.

[10] The Five Books of Moses, R. Alter, trans., New York, Norton, 2004, p. 22.

[11] M. Luther, “The Large Catechism (1529)”, in R. Kolb and T. J. Wengert, eds., The Book of Concord : The Confessions of the Evangelical Lutheran Church, Minneapolis, Fortress, 2000, pp. 431-32.

![]()