Teaching Christian Eyes

- Lee Palmer Wandel

_______________________________

Fig. 4. P. Canisius, Institutiones Christianae

Pietatis, 1575

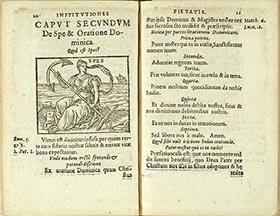

Fig. 5. P. Canisius, Institutiones Christianae

Pietatis, 1575

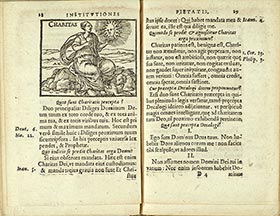

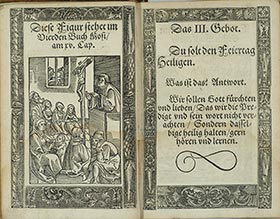

Fig. 6. M. Luther, Enchirion, 1531

Pietatis, 1575

Fig. 8. M. Luther, Enchirion, 1531

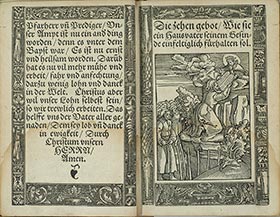

Fig. 9. P. Canisius, Institutiones Christianae

Pietatis, 1575

In turning to images, we disrupt the spatial and therefore temporal sequencing of the two authors’ catechisms. Luther began both his catechisms with the Ten Commandments. Canisius began his, as we see in fig. 3  , with the Apostles’ Creed or Symbol. In Canisius’s catechisms, the catechumen arrived at the Ten Commandments after learning the Apostles’ Creed and the Lord’s Prayer, after seeing the figures of Faith and Hope (fig. 4).

, with the Apostles’ Creed or Symbol. In Canisius’s catechisms, the catechumen arrived at the Ten Commandments after learning the Apostles’ Creed and the Lord’s Prayer, after seeing the figures of Faith and Hope (fig. 4).

In stark contrast to Luther’s catechisms, which teach the Ten Commandments as “Law”, Canisius teaches them under the rubric of “Charitasa female figure” (fig. 5). As with two other allegorical figures, Charitas marks the beginning of one section of Canisius’s catechism. The catechumen begins the catechesis of the Commandments with an allegorical figure, at once a mnemonic and itself providing the entry into catechesis. Love, not law, is the visual point of departure.

This small woodcut teaches the eyes of Canisius’s catechumens one kind of visual complexity : in her right hand, she holds her heart, in her left, a radiant sun which looks upon her heart. As the catechumen will learn, that same word, “Charitas”, which appears in the woodcut is that which is commanded and also given by God, informing the heart. The image actively participates in Canisius’s catechisms in teaching the catechumen a very different understanding of “command”. In Canisius’s catechisms, the first command is love, and that love is represented as a heart, a sun, and a female figure visually like the figures of faith and hope, the other theological virtues.

The image that opens the first section of Luther’s catechism (fig. 6) is not figurative, emblematic or allegorical. It depicts – a word Reformed Christians would problematize – a moment that would have been familiar to most Christians, when Moses received the tables from God. This particular image places Moses nearly touching those who, in the biblical narrative, would not have been there but at the bottom of the mountain. This image, then, is also not a strict narrative of the biblical moment, but visualizes the reception of the tables as a communal event.

The Institutiones has only three images for the section on the Ten Commandments. The second (fig. 7) serves as an exemplum of the third command, “remember the Sabbath”, depicting attentive lay men, women, and children circling a preacher in a pulpit. At the same time, it also visually explicitly rejects the Reformed numbering and emphasis, in which the prohibition against images was a separate Commandment, the Second : on an altar in the back of the space can be seen a triptych of the Crucifixion.

Those of Luther’s catechisms that were published with woodcuts typically placed an image with each Commandment. For many of the Commandments, the woodcut was labeled as rendering a specific moment narrated in Scripture – again, normally, in the Old Testament. Those images offered an exemplum of the transgression drawn from the biblical narrative, such as the Golden Calf or Cain slaying Abel.

This image (fig. 8) is all the more startling, therefore, for the presence of the Crucifix that divides the plane of the woodcut. It alludes, in the gesture of the preacher, whose hair invokes Luther, to the predella of Wittenberg Altarpiece. The woodcut in the catechism is labeled, “This figure stands in the fourth Book of Moses, (Numbers), at the 15th Chapter”. In that chapter, God tells Moses how the Israelites are to worship him: with sacrifices, votives, gifts, fringed robes, and following his Commandments. And yet, the woodcut manifestly cannot be a mere depiction of Numbers 15. The crucified Christ, rendered in line, disrupts any simple equation. The crucified Christ recasts “the Sabbath” : no longer a Jewish holy day, but the Christian Sunday, in which the pious attend to the preaching of Christ, mothers teach their infants to turn towards the Word, and listening, as the figure in the lower right models, is obedience. The crucified Christ also reframes the Commandment as belonging to a continuum of divine revelation.

The woodcut complicates the temporal sequence of Luther’s catechism, which moves in the spatial logic of the codex from the Ten Commandments, to the Apostles’ Creed, to the Lord’s Prayer, ending with the sacraments. The catechumen moves in Luther’s catechisms, in other words, from Law to Grace. But the image visualizes the abiding presence of that grace, enacted in the sacrifice of the cross, at all times in a Christian’s life.

While they share with Luther’s the spatial structuring of a temporal process of catechesis, as materialized in the codex, Canisius’s catechisms begin in a different moment, with the Apostles’ Creed (fig. 3  ). They reject in their structure both the chronology Luther structures – from Old Testament to New – and the trope of Law and Grace. Instead, as the page on the left side of fig. 3

). They reject in their structure both the chronology Luther structures – from Old Testament to New – and the trope of Law and Grace. Instead, as the page on the left side of fig. 3  manifests, Canisius’s catechism also teaches liturgical time. And on the very first page of the catechism proper, the allegorical figure of Ecclesia appears. She will reappear elsewhere in the catechism, by that repetition, to one of which we shall turn below, at once providing an emblem that itself acquires more meaning through the process of catechesis and a kind of icon of the Christian’s experience of the liturgy.

manifests, Canisius’s catechism also teaches liturgical time. And on the very first page of the catechism proper, the allegorical figure of Ecclesia appears. She will reappear elsewhere in the catechism, by that repetition, to one of which we shall turn below, at once providing an emblem that itself acquires more meaning through the process of catechesis and a kind of icon of the Christian’s experience of the liturgy.

The woodcut of Ecclesia is immediately followed by two more woodcuts, both allegorical, both named by words which, in turn, acquire connotations through the images (fig. 9). The page on the left, the verso of the opening page, presents figurations of Hope, Charity, and Faith. The words Faith, Hope, and Charity appear immediately below the image, but the three figures do not correspond to the sequence of words, as the catechumen will learn in following the codex : Hope, with her anchor, is to the left; Charity, with her children, is at center; and Faith, who holds a chalice, for the sacraments, and a cross, for the offices of Christian justice, is at right.

On the facing page is a strikingly different figure of “Faith”. She sits atop a bearded Mohammed, who twists to look up at her. In one hand, she holds yet another figuration of Ecclesia, a small church with spire and three crosses, towards which she is turned. In the other hand, her left, she holds a codex, in which there is illegible writing. As the catechumen looks at the woodcut, he learns the catechism’s definition of faith : “the gift of God, and light, by which illumination humankind firmly assents to all that God reveals and proposes to us, through his church, to be believed, that which is written, that which is not”. Revelation, in Canisius’s catechism, is not restricted to Scripture, but it comes through the Church, both the figure who precedes the entire catechism on that first day, and the architectural space within which liturgy – and ideally catechesis – takes place.

![]()