“Pulsating with Life”: Young British

Artists and the Great War

- David Boyd Haycock

_______________________________

The younger Nevinson had been under contract for a one-man show in London but, overwhelmed by a sense of futility in the face of what was now happening, had been released by his dealer. In France his father had seen the appalling state of wounded soldiers left to die in railway sheds at Dunkirk, and was determined to do something. Richard Nevinson took a crash course in motor engineering and first aid, and joined the Friends’ Ambulance Unit, a Quaker organisation Henry had helped to establish [12]. In November 1914 the Nevinsons and their colleagues arrived in Dunkirk and set to work in a railway shed known as “the Shambles” – and archaic word for a butcher’s slaughterhouse. It was packed with 3,000 dead, wounded and dying French, British and German soldiers, crying pitifully for their mothers. Nevinson later recalled how they lay “on dirty straw, foul with old bandages and filth, those gaunt, bearded men, some white and still with only a faint movement of their chests to distinguish them from the dead by their sides” [13]. Nevinson worked as “nurse, water-carrier, stretcher-bearer, driver, and interpreter”, and as he later recalled, gradually “the shed was cleansed, disinfected and made habitable, and by working all night we managed to dress most of the patients’ wounds”. After a week Nevinson’s former life seemed “years away”. After a month he felt he had been “born in the nightmare. I had seen sights so revolting that man seldom conceives them in his mind”. But there was no shirking. “We could only help, and ignore shrieks, pus, gangrene and the disembowelled” [14]. It was all “a sudden transition from peaceful England, and I thought then that the people at home could never be expected to realize what war was” [15]. After the Shambles, Nevinson worked briefly as an ambulance driver. Near Ypres a shell passed clean through the back of his vehicle. Grim sights included a dead child in a Dunkirk street, killed during one of the first ever air raids. With his rheumatism worsening, however, Richard found the driving hard going, and he returned to nursing duties. After some ten weeks in France he was sent home as medically unfit. By the end of January 1915 he was back home in London.

Though brief, Nevinson’s first taste of war had been appalling. Yet once back in London he rediscovered his Futurist loyalties: he sent a photograph to Marinetti of himself posing in uniform by his ambulance, and baosted of his Front line experiences in a series of newspaper articles. In “A Futurist’s View of War”, published in The Daily Express on 26 February 1915, he declared: “All artists should go to the front to strengthen their art by a worship of physical and moral courage and a fearless desire of adventure, risk and daring and free themselves from the canker of professors, archaeologists, cicerones, antiquaries and beauty worshippers.” Though he explained that unlike his “Italian friends”, he did not “glory in war for its own sake”, and could not “accept their doctrine that war is the only health-giver”, he did not publicly renounce his allegiance to the movement. War was “a violent incentive to Futurism” and “there is no beauty except in strife, no masterpiece without aggressiveness.” He believed the “Futurist technique” was “the only possible medium to express the crudeness, violence and brutality of the emotions seen and felt on the present battlefields of Europe” [16]. Having announced his intentions in print, he proceeded to show how it could be done in paint.

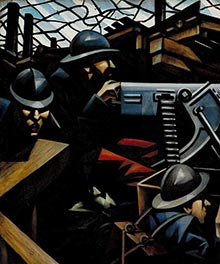

What followed was a series of remarkable prints, drawings and paintings of marching columns of soldiers, exploding shells, ruined towns and battling aeroplanes. They included such works as Column on the March (1915, Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery), La Patrie (1916, Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery) and French Troops Resting (1916, Imperial War Museum, London). The most important, and the most successful, of them was La Mitrailleuse (1915, Tate Gallery, London, fig. 1). As the critic C. Lewis Hind wrote in The Evening News when the painting was exhibited with The London Group in March 1916:

And the gunners? Are they men? No! They have become machines. They are as rigid and as implacable as their terrible gun. The machine has retaliated by making men in its own image… The crew and the gun are one, equipped for one end, only one – destruction. Horrible! [17]

The eminent painter and critic Walter Sickert declared in the Burlington Magazine that “Mr Nevinson’s “Mitrailleuse” will probably remain the most authoritative and concentrated utterance on the war in the history of painting” [18].

How had Nevinson achieved this transition from pre-war ridicule and attack, to one of praise? As Frank Rutter explained in The Sunday Times, La Mitrailleuse was “sufficiently “futurist” to be piquant and distinguished, yet no so relentlessly futurist … as to be bewilderingly disintegrated” [19]. Furthermore, cultural critics at large were starting to accept the modernist vision of the avant-garde: it was young men who were making the greatest sacrifice in a war that could be compared to no other in history. Only they could be expected to depict it – and it had to be accepted on their own, modernist terms. Nevinson’s picture was bought anonymously and presented to the Contemporary Art Society. They in turn gifted it to the Tate Gallery. As Nevinson himself subsequently explained in 1937, “My obvious belief was that war was now dominated by machines and that men were mere cogs in the mechanism” [20]. Today, the many painted representations of the conflict are so embedded in our consciousness that it is difficult to realise that Nevinson was the first person in England to represent the Great War as this hideous, corrupting, faceless mechanism for mass annihilation. As he claimed, he was the first fully to acknowledge in paint that the traditional opinion, “that the human element, bravery, the Union Jack, and justice, were all that mattered”, was plainly wrong in the face of the devastating, mutilating effects wrought by machine guns, aeroplanes and massed artillery batteries [21]. After the war Nevinson wrote: “It was said I believed man no longer counted. They were wrong. Man did count. Man will always count. But the man in the tank will, in war, count for more than the man outside” [22].

[12] Henry Nevinson, Diary, Bodleian Library, Oxford, Eng. Misc. e.618/3, November 1914.

[13] C.R.W. Nevinson (1937), 71-2; H. Nevinson, Diary, Bodleian Library, Oxford, Eng. Misc. e.618/3, November 1914.

[14] C.R.W. Nevinson (1937), 74; Henry Nevinson, Diary, Bodleian Library, Oxford, Eng. Misc. e.618/3, 14 November 1914.

[15] C.R.W. Nevinson (1937), pp. 71-72.

[16] Michael Walsh (2002), p. 98.

[17] C. Lewis Hind, The Evening News, 16 March 1916.

[18] Walter Sickert, The Burlington Magazine, April 1916.

[19] The Sunday Times, 5 March 1916.

[20] C.R.W. Nevinson (1937).

[21] Ibid., p. 87.

[22] Ibid., p. 85.