The Woman in White, White Space

and Mid-Victorian Print Technology

- Mary E. Leighton - Lisa Surridge

_______________________________

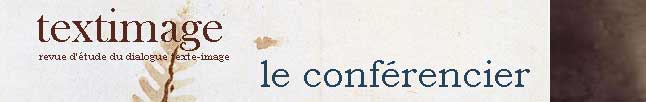

Fig. 10. J. McLenan, The Woman

in White, 1860

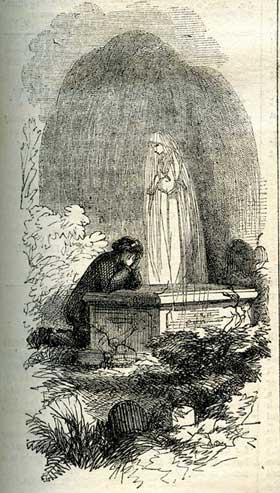

Fig. 11. J. McLenan, The Woman

in White, 1860

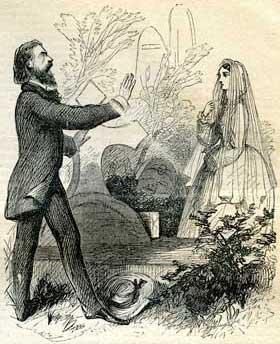

Fig. 12. J. McLenan, « The nurse came quickly

around the corner of the wall... », 1860

The novel’s most sensational scene occurs when Hartright goes to mourn Laura at her grave (which will later be revealed as Anne’s rather than Laura’s). While he is there, he sees two veiled women approaching, who turn out to be Marian and Laura; however, Hartright does not recognize Laura until she lifts her veil, which is when she stands directly over the gravestone inscribed with her death date. In this, the novel’s pivotal scene, the verbal trope of repetition reaches its climax, with Hartright taking on the speech pattern hitherto associated with Anne Catherick:

Above it, there were lines on the marble, there was a name among them which disturbed my thoughts of her. I went round to the other side of the grave, where there was nothing to read – nothing of earthly vileness to force its way between her spirit and mine.

I knelt down by the tomb. I laid my hands, I laid my head on the broad white stone, and closed my weary eyes on the earth around, on the light above. I let her come back to me. Oh, my love! my love! my heart may speak to you now! It is yesterday again since we parted—yesterday, since your dear hand lay in mine – yesterday, since my eyes looked their last on you. My love! my love! […]

Beyond me, in the burial-ground, standing together in the cold clearness of the lower light, I saw two women. They were looking toward the tomb; looking towards me.

Two.

They came a little on; and stopped again. Their vails [sic] were down, and hid their faces from me. When they stopped, one of them raised her vail. In the still evening light I saw the face of Marian Halcombe.

Changed, changed as if years had passed over it! The eyes large and wild, and looking at me with a strange terror in them. The face worn and wasted piteously. Pain and fear and grief written on her as with a brand.

I took one step towards her from the grave. She never moved – she never spoke. […]

The woman with the vailed face moved away from her companion and came toward me slowly. Left by herself, standing by herself, Marian Halcombe spoke. It was the voice that I remembered – the voice not changed, like the frightened eyes and the wasted face.

“My dream! my dream!” I heard her say those words softly in the awful silence. She sank on her knees, and raised her clasped hands to the heaven. “Father! strengthen him. Father! help him, in his hour of need.”

The woman came on – slowly and silently came on. I looked at her – at her, and at none other, from that moment […]

The woman lifted her vail.

Sacred

TO THE MEMORY OF

LAURA,

LADY GLYDE –

This passage is saturated with figures of repetition: 1) anaphora, wherein words repeat at the beginnings of phrases; 2) epistrope, wherein words repeat at the ends of phrases; 3) anadiplosis, wherein the first word of a phrase repeats the last word of the previous phrase; and 4) epanalepsis, wherein words repeat after intervening matter. The effect is similar to homiologia in that, after a certain saturation of repetition, meaning is evacuated, rather than reinforced. The passage thus creates its sensational effect by evoking in Hartright’s voice Anne’s verbal tic of repetition over Laura’s gravestone (which is really Anne’s grave) while Hartright sees Laura (without recognizing her).

At the same time, the visual text in Harper’s Weekly evacuates all perspective from Laura’s figure (figs. 10 et 11): she is no longer three-dimensional but flat—that is, depicted by white space with a mere outline. Paradoxically, these visual depictions affirm her association with ghosts at the very moment when she appears in the flesh, alive. Moreover, the verbal text evacuates meaning from the gravestone inscription: if Laura is alive, then the engraved letters are literally and metaphorically hollow.

From this point on, the novel becomes an investigation of these contradictions, a setting to rest of their sensational effects. Now dead, Anne disappears from the temporal present of the narrative, appearing only analeptically. In terms of illustration, the disquieting visual conflation of Anne with Laura disappears as Laura becomes progressively more three-dimensional, acquiring bodily solidity and visual darkness in her depictions (fig. 12). Notably, Hartright never goes to court to seek legal confirmation that Laura is not dead. Instead, he and Marian resort to narrative (telling the story of the conspiracy) and then to visual evidence (showing Laura to the tenants on the estate to prove her identity). What they provide, then, is not legal proof but a multiplication of narratives, one substituted for the other. Only then do they efface the inscription on her gravestone, chiseling out Laura’s name so that only a blank space remains, to be re-engraved later with Anne’s name.

[20] Ibid., May 19th 1860, p. 311.